A Southwest Success Story at Watershed Scale

If a person were to park on the border of Arizona and Nevada, step out of their vehicle, and start walking east across the Bureau of Land Management’s Arizona Strip District, it would be many days, perhaps even weeks, before they reached the other side. The scale of the landscape is nearly incomprehensible. There is little water to be found, and depending on the time of year, temperatures soar well above 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

So in this vast corner of Arizona, how are managers implementing projects that can stand up against the mounting challenges of climate change, expanding trees and other woody species, invasive grasses, wildfire, and more?

They’re thinking big. Watershed- and landscape-scale big, to be exact.

“We’re looking at this landscape as a whole and being more strategic, instead of throwing darts at a dartboard,” says Stephanie Grischkowsky, a wildlife biologist with the BLM’s Arizona Strip District.

Grischkowsky and her colleagues are breaking down the challenges they’re faced with on the Arizona Strip and seeing tangible, lasting benefits as a result.

A satellite view of the BLM Arizona Strip District, with a yellow star highlighting the story area.

The BLM’s Arizona Strip District manages 2.8 million acres in the northwestern corner of Arizona, balancing many resource values including wildlife habitat, forage for livestock grazing, and important cultural areas. Hundreds of species of wildlife call this land home including pronghorn, mule deer, pinyon jays, bighorn sheep, and California condors. Ranchers utilize grazing allotments for cattle. Visitors come from across the globe to enjoy the recreation opportunities and solitude. And at the helm, land managers must take all interests into account when planning and implementing projects.

For Ben Ott, a rangeland management specialist with the Arizona Strip District who has worked on this landscape for decades, it’s important to think about project impacts far beyond the present or near-future. One of those projects is Buck Pasture Canyon.

Buck Pasture Canyon lies within the Buckskin Mountains on the eastern side of the District, sitting on a plateau high above the sunbaked valley floor. Driving into the area, it’s instantly clear how successful this project still is more than a decade after its implementation in 2009.

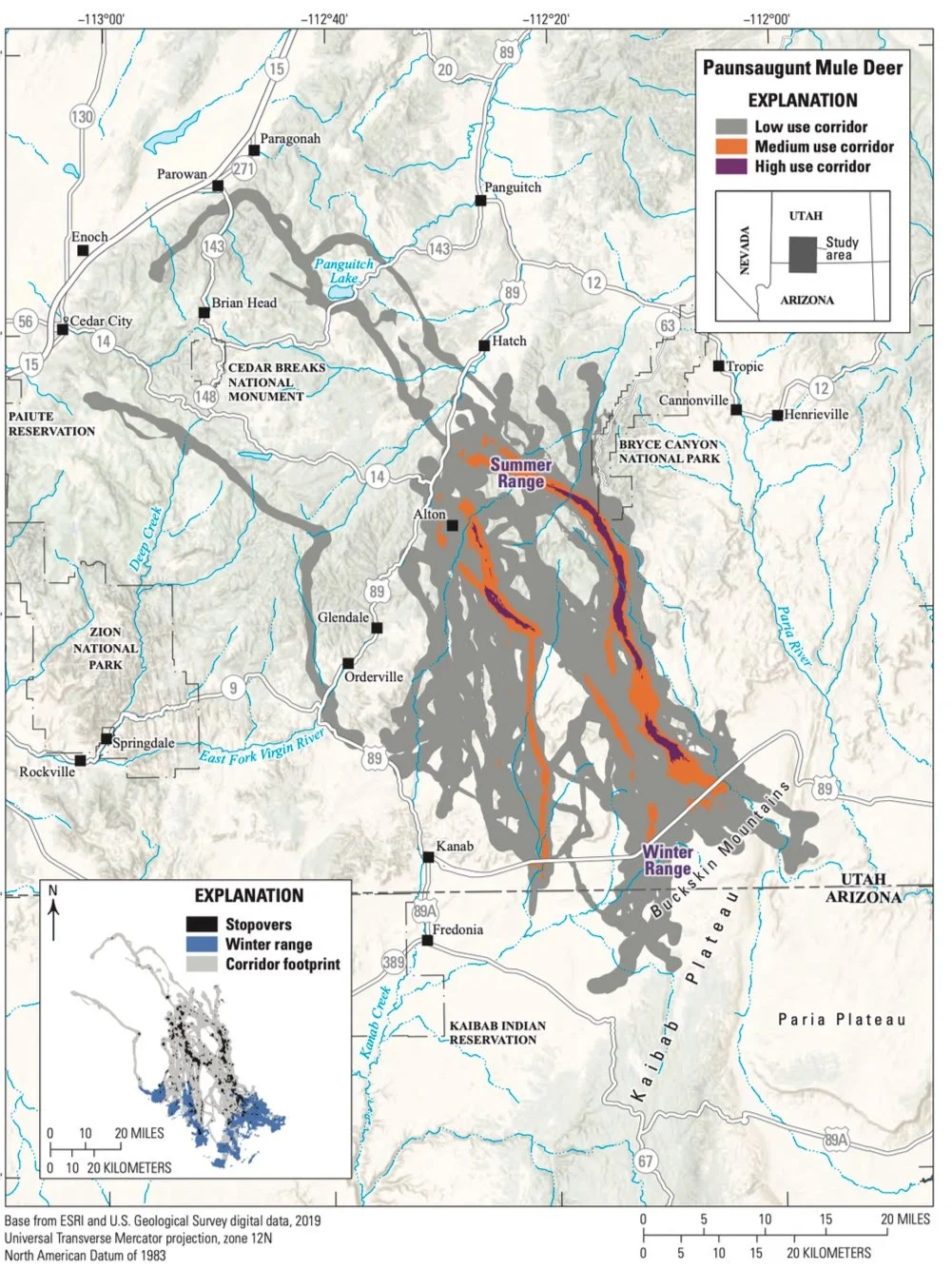

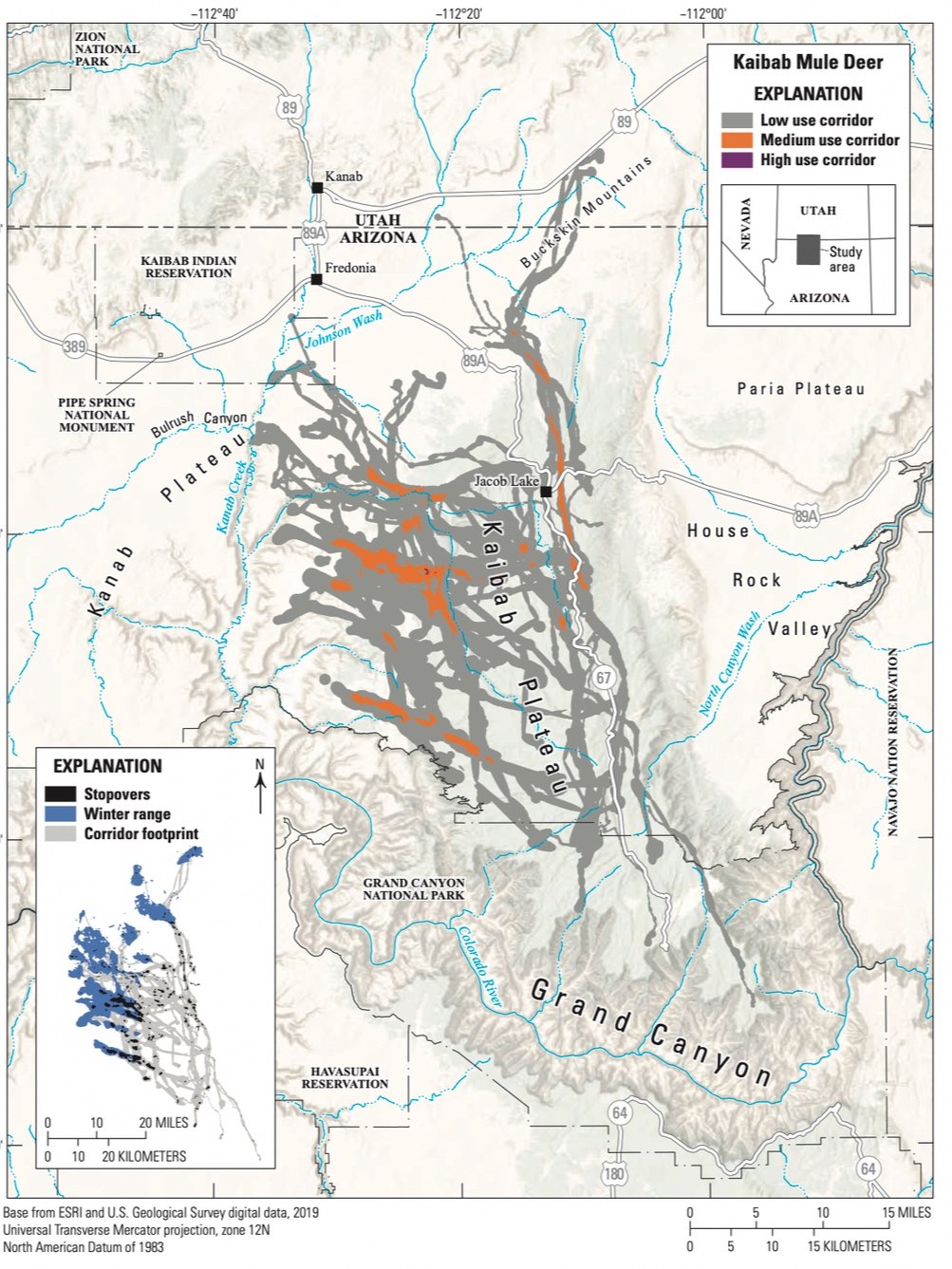

First proposed as a prescribed fuels treatment, managers hoped to create a break in the expanse of pinyon and juniper trees that could moderate the advance of a large wildfire. The increasing density of woodlands here, also called infill, was causing a decrease in other ground covering native vegetation, leading to a lack of habitat diversity, little available forage for wildlife and livestock, and increased soil erosion. By clearing up to 1000 acres of trees, leaving islands of trees intact within the clearings to protect multiple resources and also provide cover for wildlife, managers not only provided a critical fuel break, but improved habitat for the Kaibab and Paunsaugunt mule deer herds whose winter ranges overlap in this particular area (shown in the U.S. Geological Survey maps above). It was a lot of bang for their buck (pun intended!), with benefits reaching far beyond the intended goal of wildfire mitigation.

“A mosaic between islands and corridors was the goal. Not using just straight lines, but also having a lot of edge habitat ratio,” said Grischkowsky.

“One of the most important things for land management is perspective”

These islands of trees and edge habitat have also been shown to provide benefits for a charismatic, blue bird, the pinyon jay. Within Buck Pasture Canyon and the surrounding area, Grischkowsky works with Arizona Game and Fish Department and the Great Basin Bird Observatory to hone in on just how pinyon jays are living within the landscape. Partners are gathering baseline data to pinpoint where and how the birds are utilizing the area and to provide this data prior to future treatments. Coupled with ongoing vegetation monitoring data, baseline pinyon jay monitoring data will help the BLM and partners determine exactly where, and where not, to put woodland management plans into action on the ground.

Also working in this unique region is Kaitlyn Yoder, Coordinating Wildlife Biologist with Quail Forever. Yoder is also an IWJV Sage Capacity Team member.

“One of the most important things for land management is perspective,” said Yoder. “We need to always remember that any given resource is a small piece in a larger functional system. That is why planning for landscapes is so productive and rewarding. Balancing objectives like wildlife habitat, fire mitigation, and livestock forage, for me, is akin to composing a symphony or painting a beautiful picture.”

Another part of this region’s composition is south from where Buck Pasture Canyon lies. Pine Hollow is a similar project, and was written through the same National Environmental Policy Act analysis, but was implemented in 2013. Cheatgrass has found footing within the Arizona Strip District and managers must now be creative about working to combat this growing threat. When listening to Ott talk about the results from Pine Hollow and how they have been able to keep cheatgrass at bay, one can easily pick up on the tinge of pride in his voice.

“We were able to stabilize the ecological site to a degree that native species are working their way back into the system. This prevents the area from crossing a threshold of cheatgrass and weed invasion,” he explained.

Ironically, the Pine Hollow project was implemented before the Pine Hollow Fire swept through more than 11,000 acres of the surrounding landscape in 2020. The tree removal effort did its job to slow the spread of fire and gave firefighters a chance to defend unburned woodlands and meadows across the plateau. Impacts from the Pine Hollow Fire can still be seen from miles away, but also visible are the long strips of green vegetation that helped slow the fire’s spread, protecting vital habitat on this semi-arid landscape.

“Often when we look back at what our predecessors have done in the name of good management we come up with criticisms,” concluded Yoder. “It may be that future land managers will do the same to us one day. Regardless of your opinion of fire or no fire, native seeding or non-native seeding, we learn so much from how the land responds to past treatments. So many factors go into the success of a treatment on the landscape, many of which are completely out of our control. The knowledge and insight past projects provide current land managers is invaluable and we would be negligent to ignore their lessons, especially the successful ones.”

Today, instead of a monoculture of thick woodlands, you’ll find a mix of open meadows, small islands of trees, miles of edge habitat, as well as healthy forbs, shrubs, and bunchgrasses within Buck Pasture Canyon and Pine Hollow. You may see cows grazing or hunters quietly sitting under a tree in the mid-morning sun. And if you’re lucky, you might even spot the oversized gray-brown ears of a mule deer or the blue flash of a pinyon jay.

Buck Pasture Canyon